Industry News

Industry News

A surge in bearing failures on newbuilds has been linked to IMOвҖҷs Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI). But should they have been spotted earlier?

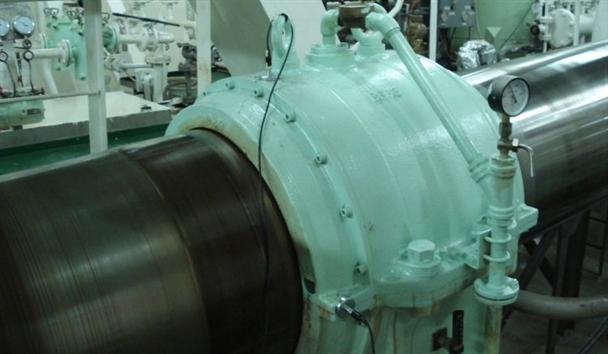

Between 2013 and 2017 an estimated 200 vessels suffered from shaft bearing failures, according to shipowner reports to ABS. Incidences appeared to slow in 2018, although it cannot be determined whether this is a result of effective intervention or the slow pace of newbuilding. From 1 January 2013, all IMO-regulated newbuilds were required to meet progressively tighter efficiency requirements under EEDI.

ABS Global Ships Systems Centre director Dr Chris Leontopoulos explains that the need for greater efficiency led to smaller enginerooms, slower rotating engines and heavier propellers connected by shorter and thinner propeller shafts. These have combined to amplify forces acting on the shaftline, resulting in increased incidences of shaft misalignment and failures in the stern tube bearings that support shafts.

Big vessels, including very large crude carriers, ultra large container ships and bigger gas carriers are particularly prone to shaft misalignment, because of the greater propulsive power and forces acting on their flexible hulls. Dr Leontopoulos notes that mid-sized vessels where the forward stern tube bearing had been removed to accommodate smaller engineroom designs were also regarded as вҖңshaft alignment sensitiveвҖқ.

Countermeasures

The impact of these changes can be reduced by using double-sloped bearings, which optimise the shaftвҖҷs contact with the bearing. вҖҳRunning inвҖҷ of bearings, by gradually rotating the propeller shaft faster before the ship is put into operation, also helps to optimise the surface area supporting the shaft.

These measures are included in updated shaft alignment rules introduced by ABS, which has also introduced enhanced shaft alignment guidance and notations. Other class societies including DNV GL and LloydвҖҷs Register have also updated their rules. Dr Leontopoulos is the manager of a project team developing the first unified requirements on shaft alignment at the International Association of Classification Societies. He expects that the first unified requirements on shaft alignment will be published next year.

вҖңBig vessels are particularly prone to shaft misalignment, because of the greater propulsive power and forces acting on their flexible hullsвҖқ

Dr Leontopoulos notes the recent controversy over environmentally acceptable lubricants (EAL) but he himself has never seen a case of stern tube failure caused solely by the use of EALs. However, he admits that mineral oils might have provided a greater safety margin in cases of extreme shaft misalignment.

Giulio Gennaro of engineering consultancy 1888 Gennaro Consulting has seen plenty of shaft bearing failures and has a different perspective on their root cause. He believes that energy efficiency regulations are being blamed for shortcoming in scantling and design. Mr Gennaro takes particular issue where reputable equipment suppliers and class societies have been responsible for designing and approving propulsion arrangements.

вҖңTo my knowledge, shaft alignment or bearing lubrication have been seldom an issue,вҖқ he says.

Rather, Mr Gennaro points to cost as the overriding issue. He cites propeller shaftlines for twin-screw installations that were designed with too small a diameter. The result was whirling problems, where the shaft vibrates uncontrollably, and consequent bearing issues. Single-bearing stern tubes and single-slope bearings were also introduced to cut costs, he says.

вҖңIn the cases I handled, all these matters would have been quite clear from the design phase, had they been duly considered,вҖқ he says. вҖңThese designs were pushed into production to reduce costs by a little, with [the] result of generating large losses later. This is not a matter of rules and regulations only вҖ“ it is a matter of the mentality of an industry that at times fails to give due consideration to technical matters.вҖқ

Design defects

Mr Gennaro cites many examples of poor design across multiple ship types. He notes several cases involving bulk carriers where the lack of a forward bearing вҖ“ along with the use of a single-sloped bearing and a high static pressure вҖ“ created вҖңhigh or borderlineвҖқ working conditions for propeller shaft bearings. In all cases, says Mr Gennaro, the issues should have been apparent in the design phase and should have been avoided.

вҖңThis is not about rules and regulations, it is about the mentality of an industry that at times fails to give due consideration to technical mattersвҖқ

In some of these cases a high eccentric thrust from the propeller was blamed for a failure of the propeller thrust bearing. But such thrust should be considered within safety coefficients, he says. Further, the full wake of the vessel is never modelled at full scale, meaning that a detailed calculation of eccentric thrust is seldom made. This can lead to uncertainty for propeller designers.

The problems are particularly galling where they are due to faulty design on the part of reputable companies. Mr Gennaro recalls a case he investigated on board a series of roro vessels where вҖңa major European supplier of propulsion packagesвҖқ had skimped on shaft diameter. As the shafts were quite long, as is often the case on roro vessels, the resulting ratio between the length and diameter of the shaft was outside of the recommended values.

вҖңThe big issue is that design errors are usually not covered by the insurance policy,вҖқ Mr Gennaro explains. вҖңTherefore, the owners select a different and more manageable alleged cause of the damage [to claim for]. This is why these incidents don't make it into the statistics despite being quite frequent.вҖқ

Monitoring shaft condition

As a leading provider of shaft bearings and seals, Wärtsilä is keeping a close eye on the reports of stern tube bearing failures , says UK sales development manager Matthew Bignell. The launch of a shaft monitoring system, Sea-Master at SMM Hamburg in 2016, was timely given the emerging concerns.

The Wärtsilä Sea-Master monitors shaft bearings and seals, collecting real-time data from the tail shaft and providing insights into the operational health of the shaft line. The system is available for all ship types and for retrofit as well as newbuild applications.

вҖңMonitoring is key,вҖқ says Mr Bignell. вҖңWe are seeing a lot of newbuild activity within shortsea shipping and feeder ships. They work in some pretty demanding environments; they may have gone down the route of choosing water-lubricated bearings and they will need to maintain uptime. ThatвҖҷs where weвҖҷll see the monitoring really paying off.вҖқ

The monitoring system is especially useful for twin-shaft vessels, where wear may be confined to one particular bearing on one of the shafts. Real-time monitoring can identify this and allow for specific maintenance. вҖңThere may be minimal wear in the inner bearings, but the outboard is wearing faster,вҖқ says Mr Bignell. вҖңYou can bring those in, whereas previously you would have changed them all. ThatвҖҷs a big cost.вҖқ

The company is planning to upgrade the system later this year to improve how it can integrate with a vesselвҖҷs energy management system вҖ“ meaning one less screen for engineers to look at. The focus, says Mr Bignell, will be on making the system more affordable, accessible and integratable. With the issues around driveline condition becoming increasingly important, it may be perfect timing.